King Charles I in Westminster: His life, execution and survival beyond death.

As I write this blog post we have just passed the 372nd anniversary of the execution of Charles I, outside the Palace of Whitehall in the heart of ‘royal’ Westminster.

His death marked an end to what is always referred to as ‘The English Civil War’. Various English monarchs have met a bloody ending, perhaps murdered by a rival claimant or in battle, but Charles I was the only king to be killed using some form of legal process and with the support of a large part of the population.

English Civil War 1642 – 1649

As kids we learn these basic facts: Charles I and Parliament had a right royal falling out, civil war just kind of happened, monarchist Cavaliers fought parliamentary Roundheads and under the leadership of Oliver Cromwell the parliamentary forces won the war. Charles I believed in the ‘divine right of kings’, would not bow to Parliament and so they chopped off his head.

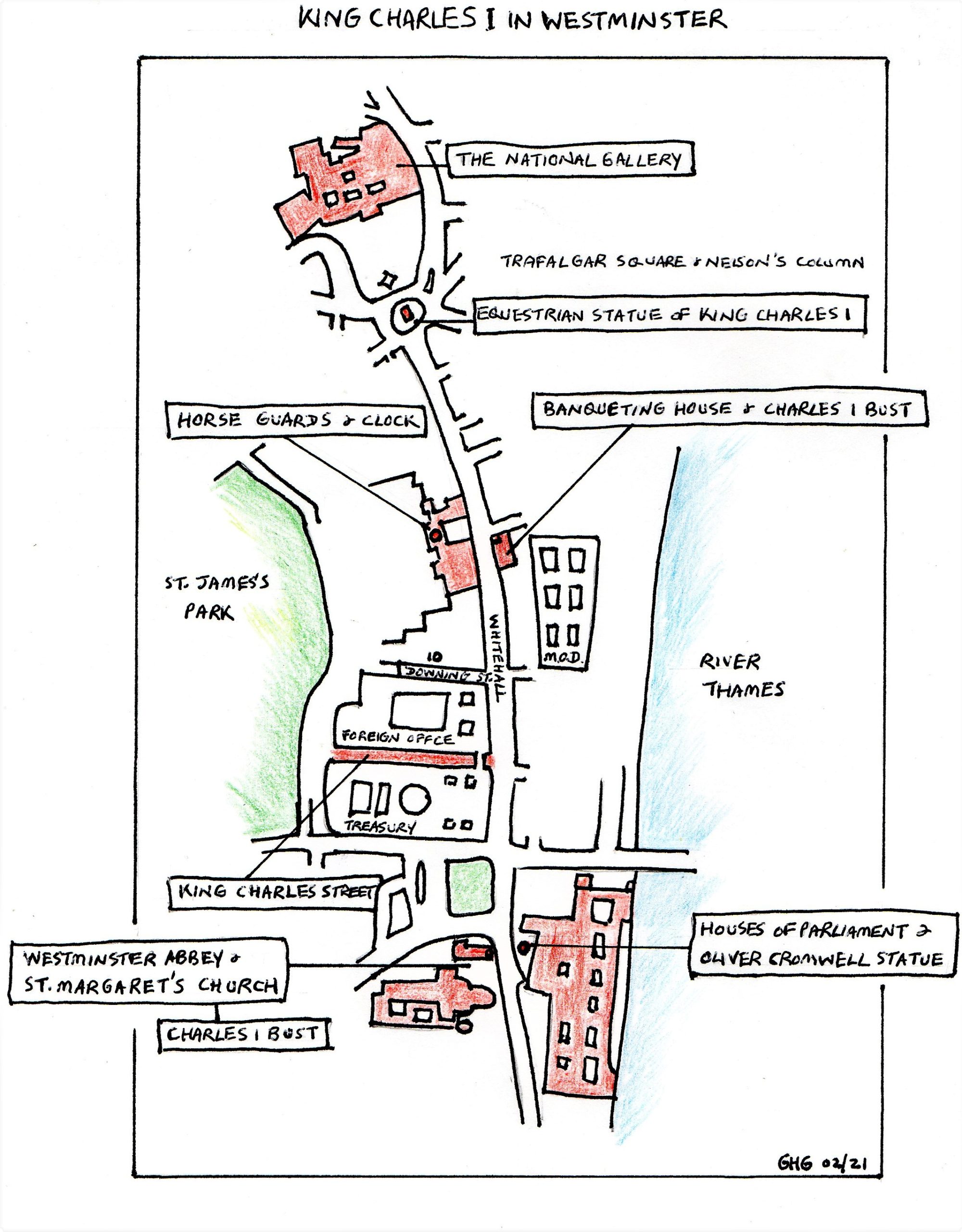

Well, do I need to say it’s quite a bit more complicated than that? People are still arguing about it, and taking sides. However this is not a blog about the civil war. It’s all about how, if you know where to look, King Charles I is visible all over Westminster, still.

King Charles I: Life and Death

Born: 19th November 1600, Dunfermline Palace, Fife – second son of King James VI of Scotland (who become James I of England in 1603, thus the Union of the Crowns) and Anne of Denmark. It’s interesting to note that in Scotland Queen Elizabeth II is technically Elizabeth I and only known by her regnal number, north of the border, through Royal Prerogative.

Reigned: 27th March 1625 – 30th January 1649.

Died: Tuesday 30th January 1649, 2.00pm at Banqueting House, Whitehall Palace, Westminster.

Buried: St George’s Chapel, Windsor Castle (9th February 1649), without ceremony he was reposed in the vault of Henry VIII.

Wife: Henrietta Maria, daughter of King Henry IV of France. The US state of Maryland (Terra Mariae) was named in her honour.

Children: Four sons, five daughters (six survived infancy), including King Charles II and King James II. Their sister Mary married William II, Duke of Orange in the Netherlands. James II was the father of Queen Mary II and Mary of Orange was the mother of King William III. That’s correct; these first cousins married and became the only monarchs to rule jointly as William & Mary.

English Civil War: 1642 – 1649. An estimated 6% of the population died – 300,000+. Conflict spread through all four nations of the kingdom and in this respect it was a lot more than an ‘English’ civil war.

The trial and execution of King Charles I

Charles’s trial by Parliament, on charges of high treason and ‘other high crimes’, began on 20th January 1649 in Westminster Hall. Charles was accused of treason against England by using his power to pursue his personal interest rather than the good of the country. He refused to recognise the court and sat mainly in silence throughout the trial. On 27th January he was declared guilty and sentenced to be ‘putt to death by the severinge of his head from his body.’

After spending his final night at St James’s Palace Charles walked (or was possibly carried in a sedan chair) to Banqueting House, which was a part of his main royal palace at Whitehall. The king was beheaded in front of a large crowd on a scaffold constructed outside the central balustrade windows.

Charles I official title was ‘Charles, by the Grace of God, King of England, Scotland, France and Ireland, Defender of the Faith, etc.’ The addition of ‘France’ was used by every English monarch from Edward III to George III, even though minimal or no French territory was held by the crown. The regicides who signed his death warrant referred to him simply as ‘Charles Stuart, King of England.’

Equestrian Portrait of Charles I, National Gallery, Trafalgar Square, WC2

circa 1637-8, Anthony van Dyck

In 1625 King Charles I succeeded his father James I as king. Van Dyck became his Principal Painter in Ordinary and was knighted in 1632. The king was a great art collector and commissioner – the ceiling paintings in Banqueting House by Rubens were commissioned by Charles I and are the only ceiling paintings by Rubens still in-situ. Van Dyke was one of Europe’s finest artists and quite a catch for the royal court. He became an expert at creating images of Charles I which expressed the king’s belief in his divine right to rule.

This fine, huge painting covers two horizontal canvases. The higher parts are very loosely painted (well, who’d look?) and it is one of only two equestrian van Dyke paintings. The other one is still owned by the Crown.

The painting shows Charles I mounted on a large horse surveying the landscape of England. He is wearing the medallion of a Garter Sovereign and riding as if at the head of his knights. He is dressed in Greenwich-made armour and holding a commander’s baton. He is both glamorous and ready for battle.

The horse is wearing gold decoration and has an elegantly styled main which blows in the breeze, as does the King’s. It’s a muscular beast, entirely suitable for carrying such a high status rider. With one hand Charles I confidently controls this powerful animal, demonstrating his greater strength, which is the power to command his nation.

A page to the king’s right carries his helmet. The union of kingdoms is commemorated in latin on the tablet tied to the tree: CAROLVS/REX MAGNAE/BRITANIAE (‘Charles, King of Great Britain’).

In 1652 Parliament sold the painting as part of ‘The Commonwealth Sale’ to pay off debts both the king and Parliament had accrued. It returned to England in 1706.

Anthony van Dyke (1599 – 1641).

Van Dyck was regarded as the most important Flemish painter of the 17th century after Rubens.

In 1621 he was in the service of James I of England, but left to visit Italy and then the Netherlands. Van Dyck returned to the English court in 1632. His masterful and flattering representations of Charles I and the royal family set new standards and styles for English portraiture.

Van Dyke was buried in old St. Paul’s Cathedral but his tomb was destroyed in the Great Fire of London (1666).

Equestrian Statue of Charles I, Charing Cross, SW1

Date: statue 1633, pedestal 1675.

Sculptor: Hubert Le Sueur (c1580 – c1660).

Architect (pedestal): Sir Christopher Wren.

Materials: Bronze statue, Portland stone pedestal (reliefs by Joshua Marshall – Stuart coat of arms).

Dimensions: Statue – 9’ high x 8’ head to tail. Pedestal – 14’ high x 10’ long x 5’ 6” wide.

Hubert Le Sueur was a French sculptor at the royal court who moved to London by royal command when Charles I married Henrietta Maria, daughter of the French king, in 1625. He brought the technique of bronze casting with him. Two of his tombs survive in Westminster Abbey and a bust of Charles I in the Victoria & Albert Museum. This statue is his most famous work before returning to France c1642. It is the first Renaissance style equestrian statue produced in England.

The original commission was by Sir Richard Weston, Lord High Treasurer, and the statue was to be displayed on his estate in Roehampton, near Putney.

When the contract for the statue was being written it was stipulated that the horse should be bigger than a ‘greate horse by a foot’ and that the king should be ‘a full six foot’. Charles I was actually 5’ 4”. Le Sueur was also to take the Kings advice during all stages on shape and pose. Le Sueur’s fee was agreed at £600.

Weston became first Earl of Portland but died in 1635 and although the statue was completed it was never installed. During the Civil War its ownership fell into dispute but at some point a brazier from Snow Hill called John Rivett took ownership and was ordered (and presumably paid) by Parliament to melt it down.

Instead it seems Rivett buried the statue in his garden. Stories, perhaps urban myths, begin to take over here. It’s claimed that Rivett sold scraps of bronze to tearful monarchists, who believed them to be souvenirs from the statue, so that they could own a ‘relic’ connected to their martyred king; and that he also sold similar scraps of bronze to Parliamentary supporters so they could gloat in triumphalism. It also seems that plenty of people knew the statue, in its entirety, had been hidden.

The widow of the second Earl of Portland regained ownership after the restoration of the monarchy and sold it to Charles II for £1600. That’s a profit of 266% between commission and final sale, with John Rivett allegedly making money through nefarious means during the intervening years as well.

The king paid Sir Christopher Wren to design a pedestal, with Joshua Marshall as the stone carver. In 1676 Charing Cross was chosen as the site for the completed statue; a royal symbol to replace the original Eleanor Cross which had been destroyed during the Civil War (the Eleanor Cross standing outside Charing Cross Station is a Victorian reproduction). It so happens that this was also the spot at which Charles II had some of his father’s surviving regicides executed.

As the most public image of the ‘Martyr King’, a wreath is laid at the base of the pedestal in his memory every 30th January.

Banqueting House, Whitehall, SW1

Banqueting House is the only remaining building from the Palace of Whitehall, the main London residence of English monarchs from 1530 to 1698 (when most of the palace was destroyed by fire). The building is significant in the history of English architecture as one of the first structures to be completed in the neo-classical style; a style which was to transform English architecture.

After the timber Banqueting House burnt down in 1619 King James I commissioned a new one. Designed by Inigo Jones in an Italianate style influenced by Andrea Palladio, the new Banqueting House was constructed using three different colour stones and completed in 1622 at a cost of £15,618. The building was controversially re-faced in white Portland stone in the 1830s, although the details of the original façade were faithfully preserved.

Execution of Charles I

On 30th January 1649 King Charles I was bought here for his execution. He was escorted under guard from St James’s Palace, where he had been confined, to the Palace of Whitehall. An execution scaffold had been erected in front of Banqueting House.

At about 2.00pm the King stepped through an opening somewhere to the left of the large central balustrade windows onto the scaffold and made a speech to the assembled crowd. He then knelt, said a prayer and put his head on the block, signalling to the executioner when he was ready by stretching out his hands. He was then beheaded with one clean stroke. According to an observer, the preacher Philip Henry, ‘there was such a groan…as I never heard before and desire I may never hear again’ from the crowd, some of whom then dipped their handkerchiefs in the king’s blood as a memento.

Although Charles’s head was held up to the crowd the hooded executioner, perhaps to maintain his anonymity, didn’t say ‘Behold, the head of a traitor’.

Bust of Charles I

Positioned in a niche above the small north western door of Banqueting House is a lead bust standing 20” high, based on Anthony van Dyke’s triple portrait of Charles I displayed in Windsor Castle.

It is one of a pair of ‘mystery’ busts of unknown origin; possibly late 19th or early 20th century. The other bust sits in a niche over the east door of St Margaret’s Church opposite Old Palace Yard (see below). Both were installed in 1956.

They were purchased c.1950 from a Putney antiques dealer by the barrister Hedley Hope-Nicholson, who was on the committee of the Society of King Charles the Martyr. It has been suggested that Charles stepped onto the scaffold through an opening on a long-demolished annexe, approximately where the bust sits today.

Horse Guards, Whitehall, SW1

Horse Guards was built in the mid-18th century, replacing an earlier building, as a barracks and stables for the Household Cavalry. Horse Guards also functions as a gatehouse giving access between Whitehall and St James’s Park via gates on the ground level and Horse Guards Parade.

It originally formed the entrance to the Palace of Whitehall and later the approach to St James’s Palace; for this reason it is still ceremonially defended by the Queen’s Life Guard and Blues & Royals. It is still symbolically the beginning of the royal route to St James’s Palace and Buckingham Palace.

The first Horse Guards building was commissioned by Charles II in 1663, on the site of cavalry stables which had been built on the tiltyard of the Palace of Whitehall during the Commonwealth of the 1650s.

Following the fire at Whitehall Palace in 1698, Horse Guards was increasingly used as offices for the growing regular army and it soon became overcrowded. The fabric of the building also deteriorated. In 1745 King George II commissioned a new building in the fashionable Palladian style, designed by William Kent. Kent died in April 1748 and work on the new building commenced in 1750 under the direction of Kent’s assistant, John Vardy. The cost of the buildings was £65,000 and took nearly ten years to complete.

The Household Cavalry Museum is also housed in the building and government offices.

The Clock

The clock is sited in the turret above the main archway. It has two faces, one facing Whitehall and the other Horse Guards Parade. Each dial is 7’ 5” in diameter and it strikes the  quarter-hour on two bells. Originally dating from 1756, the clock was rebuilt in 1815.

quarter-hour on two bells. Originally dating from 1756, the clock was rebuilt in 1815.

Prior to the completion of the clock of Big Ben in 1859, the Horse Guards Clock was the main public clock in Westminster.

A black spot above the Roman number two on the clock face marks the hour of 2.00pm, the time of the execution of Charles I in 1649, which took place in the roadway directly opposite Horse Guards.

King Charles Street, SW1

This often missed quiet street runs from Parliament Street to Horse Guards Road, with the Foreign Office to the north side and the Treasury to the south side. There is a 50/50 chance that it’s named after Charles I.

From its beginnings in the late 1600s to the early 1900s it was simply called Charles Street. It’s a survivor too. The warren of tiny streets and alleys that used to border Charles Street have all disappeared, covered over by the two huge government buildings during the mid 1800s. Gone forever are Gardeners Lane, Boar’s Head Yard, King Street, Duke Street, Delahay Street and others.

In 1908 the triple arched foot bridge was created, linking the Treasury and Foreign Office and making a grand entrance to King Charles Street. I suspect the street was renamed during this building project – the name change occurred between 1907 and 1915.

It’s a stone’s throw from old Whitehall Palace where both Charles I and his son Charles II lived and by the 20th century there were a number of Charles Street’s in London – one survives a few minutes away in St James’s. This slight tampering with the name would have differentiated it from the others. The ‘King Charles’ it refers to seems to be unimportant.

St Margaret’s Church, Westminster, SW1.

If you have ever wondered what the small white stone church next to Westminster Abbey was wonder no more. St Margaret’s was founded in the 12th century by Benedictine monks, so that local people who lived in the area around the Palace of Westminster and the Abbey could worship separately in their own simpler parish church.

St Margaret’s was rebuilt from 1486 – 1523 at the instigation of King Henry VII and is described as ‘the last church in London decorated in the Catholic tradition before the Reformation.’ It’s one of the final flowerings of English perpendicular Gothic. The coronation of King Charles I took place in Westminster Abbey on 6th February 1646.

By 1614 the Palace of Westminster was wholly devoted to Parliament. Royalty had moved out a century earlier making their bases in Whitehall or St James’s Palaces. St Margaret’s became the parish church of the Palace of Westminster when the Puritans, unhappy with the highly liturgical Abbey, chose to hold their Parliamentary services in a church they found more suitable. It is still the parish church of Parliament. There was a lot of restoration during the 18th and 19th centuries, internal and external, but many of the Tudor features survive.

Winston Churchill married Clementine Hozier here. William Caxton, regarded as the founder of printing in England and Sir Walter Raleigh are buried in the church. Raleigh had been executed outside Parliament.

Bust of Charles I

This is the second in our pair of ‘mystery’ lead busts of Charles I (see above). It also stands 20” high and is also based on Anthony van Dyke’s triple portrait of Charles I in Windsor Castle.

Like its twin this bust is also of unknown origin; possibly late 19th or early 20th century. The other bust sits in a niche over the door of Banqueting House, Whitehall. Both were installed in 1956.

They were purchased c.1950 from a Putney antiques dealer by the barrister Hedley Hope-Nicholson, who was on the committee of the Society of King Charles the Martyr.

This lead bust of Charles I is looking directly across to Parliament’s Old Palace Yard at a bronze statue of Oliver Cromwell (William Hamo Thorneycroft, 1899), outside Westminster Hall which, just as a reminder, is where the trial of King Charles was held.

Following the Restoration in 1660 Cromwell’s head was displayed on a spike near here, after his body had been dug up and symbolically ‘executed’ at Tyburn (he died the first time in 1658, in Whitehall Palace of all places). I’m not sure who decided to place Charles I face-to-face with Oliver Cromwell but it certainly seems a bit mischievous and somehow entirely appropriate.

The Houses of Parliament are where Charles attempted to arrest five members for high treason on the 3rd January 1642. By the time he entered the House of Commons to carry out the arrests, in person, the sought after members had fled. The nation was now only eight months away from the start of civil war. Since this date no monarch has been allowed to set foot in the Commons.