The National Gallery: Top 12 Highlights

Founded in 1824, the National Gallery in Trafalgar Square houses a collection of over 2,300 European paintings from the mid-13th century to the early 1900s. Every great artist from Romanesque to Renaissance and from Baroque to Impressionism is displayed here.

The National Gallery, London.

This ‘National Gallery – Top 12 Highlights’ will hopefully provide an easy-to-follow intro of sorts and a bit of focus for your first visit (although it’s really only ‘a’ top 12 because there are dozens of masters and their superb world-famous paintings displayed here).

Admission is free: 10.00am – 6.00pm.

Here is the London Explorer’s Top 12 Highlights of the National Gallery .

1. The Wilton Diptych – circa 1395-9.

Despite the National Gallery’s pan-European range and the world-renowned masters on display we’re going to begin with a remarkable English painting done by anonymous hands and of which there is no comparable work in existence.

The Wilton Diptych was created to be a portable altarpiece used for the private worship of King Richard II of England (1377-99). A diptych is a painting in two parts on two panels, oak in this case, hinged like a book (most gothic triptychs are larger non-portable altarpieces in three sections). The paintings name is from Wilton House in Wiltshire, the seat of its previous owners the Earls of Pembroke, although earlier it had been in royal hands during the reign of Charles I.

On the inside left panel Richard II is being presented by three saints to the Virgin and Child and a company of angels, on the right panel. Nearest to Richard is his patron saint John the Baptist, holding a lamb. Behind are 11th century Saint Edward the Confessor holding the ring he gifted to a pauper (who was really St John the Evangelist) and Saint Edmund (martyred by Danes in 869, hence the arrow). Edward and Edmund were English kings who came to be venerated as saints. Around Richard’s neck is the common broom, the planta genista that gave Richard’s Plantagenet dynasty its name. A lace like pattern has been hammered into the gold leaf for heightened decoration.

Wilton Diptych, National Gallery

On the inside right panel heaven is represented. Mary is holding the baby Jesus who is reaching out to Richard. Not only are two realms meeting but Jesus is acknowledging Richard personally. Mary is also showing us Jesus’ foot, a premonition of where the nails would go in his crucifixion. There are eleven angels; Richard II was eleven when he became king. Each angel wears a white hart brooch, almost like they are members of Richard’s royal court, and the impression is that Richard is being anointed by heaven. The white hart (or white stag) was Richards personal emblem. There are still a lot of ‘White Hart’ pubs to be found through England. The gold leaf, vermillion and ultra-marine in both panels would have been very expensive.

Cleaning in 1992 revealed the image in the standards orb: a white castle on a green island set in a silver sea: it is England, the sceptred isle. Richard has presented it to the child Jesus in return receiving Jesus’ blessing.

Wilton Diptych (rear), National Gallery

The exterior or rear panels feature Richard’s arms and his personal emblem of a white hart chained with a crown around its neck. It sits in a field of rosemary which is associated with Richard. The meaning of the almost obscured standard is a mystery: resurrection, Christ’s victory over death or St George? The shield has emblems of both England and France (Richard’s second wife was the daughter of the French king).

It is not known who painted the Wilton Diptych but the artists were probably from England and France. To sign a painting was not usual in the 14th century, especially if it was to be used in religious devotions. An artist’s status was that of a skilled craftsman who usually worked in collaboration with others. This is a painting in tempera – which was to be the norm for another half century – meaning the paints and colours are mixed with an egg yolk base.

Richard II was the first English king to be accurately represented in portraits. His cherubic face and long red hair are portrayed identically in a painting displayed at Westminster Abbey.

2. Venus and Mars – circa 1485, Sandro Botticelli.

Successful Renaissance artists would often receive commissions from royalty, the church or as in this case, wealthy individuals. Scenes like this from classical literature and myth were popular subjects. Mars, handsome god of war, was the lover of Venus, beautiful goddess of love. But this was an illicit love as Venus happened to be married to the not-so-gorgeous Vulcan, god of fire and metalwork. We can see Mars asleep and virtually naked and Venus, dressed chastely and unexposed, is awake and alert. The meaning of the picture is that love conquers war, or love conquers all. They are resting peacefully in a forest surrounded by playful satyrs. It is one of Botticelli’s few secular paintings and although referring to classical legend Venus’ clothing and hair and Mars’ armour are all contemporary to Botticelli’s Florence.

Botticelli, Venus and Mars – National Gallery

This work was probably commissioned to be hung in a private chamber, possibly that of a newly married couple, and most likely would have been a spalliera or backboard, hung above a chest or day bed. Displayed at eye level it created a window into different, sensuous world. The chamber would have been used for socials and sleeping and was an ideal space for the husband to show off his sophisticated but cheeky tastes.

The subject matter is both seductive and somewhat ribald, as Mars seems worn out. The lance and conch are familiar sexual symbols. Mars is clearly sleeping the ‘little death’ which comes after making love, and not even a trumpet blown in his ear will wake him. The little satyrs have stolen his lance – a joke to show that he is now disarmed.

It has also been suggested that the plant in the bottom right corner is a species of aloe, allegedly providing medicinal powers or protection against evil spirits or – as seems likely here – enhancing sexual excitement. The wasps (vespe in Italian) at the top right suggest a link with the Vespucci family, possibly the commissioners, although they may be no more than a symbol of the stings of love. It is beautifully painted and Botticelli’s technique is superb. Try and separate Venus’s hair and clothing and notice how intricately painted her dress is.

3. The Arnolfini Portrait – 1434, Jan van Eyck.

Where to start? This mysterious work is a double portrait probably of Giovanni di Nicolao Arnolfini and his first wife, Costanza Trenta, but may not be intended as a record of their marriage, as many think. In fact it may be a memorial following Costanza’s death in childbirth.

Arnolfini is greeting the artist or us or some visitors into their well-furnished bedroom – which van Eyck has filled with allegory and symbolism – as bedrooms were often used by the wealthy for greeting visitors. And by the way, look at all the paintings around you; this is the only one set in a secular, contemporary environment, although faith is present everywhere within this work. So, what is the mysterious event we are invited to? Let’s explore both theories:

The Arnolfini Portrait, Van Eyck, National Gallery

Version 1. Shoes off does symbolise a sacred event, in this case their marriage so Costanza may not be pregnant as is often thought but holding up her full-skirted dress in the contemporary fashion. Arnolfini was a member of a merchant family from Lucca living in Bruges and extremely wealthy, and she may simply be showing off how much fine cloth they can afford.

The Arnolfini’s are wearing expensive winter furs – squirrel fur for her, although the orange on the table seems to imply that it’s summer. Why? Is this simply showing us that Arnolfini imported Italian oranges to Bruges? The dog represents fidelity and loyalty and one candle in the chandelier could mean one God. Perhaps the painting was commissioned following their union to send back to the family in Lucca; it’s certainly small enough to transport easily.

Version 2. Costanza is already dead. She is represented as being pregnant but died in childbirth. The orange and the cherry tree, which can be seen through the window, represent the Garden of Eden which for Arnolfini is actually ‘paradise lost’. There is a lit candle above him, but an extinguished candle stub above her. Here may be the clincher; a carved St Margaret is praying on the bedpost; she is the patron saint of pregnant women. The pattens, or removable shoe soles, on the floor tell us his love will not wander and the dog does indeed mean fidelity, Giovanni’s to Costanza’s memory. Very touching, Giovanni did of course remarry.

Van Eyck shows off his skills in every aspect of this painting. The mirror has twelve tiny images of the Passion painted into the frame – six images representing Jesus’s life on his side and significantly six of Jesus’s death on her side. There are two people reflected in the mirror. Is it van Eyck + 1, or two visitors entering the room? Arnolfini raises his right hand as he faces them, perhaps as a greeting to us or to the relatives in Italy.

Van Eyck was intensely interested in the effects of light, perspective and geometry and he is the first painter to perfect the use of oil paint (the layering of oil paint enabled artists to paint realistically). This allowed van Eyck to depict his subjects with greater subtlety and detail. He was a genius and a revolutionary. The swirling signature above the mirror translates as ‘Jan van Eyck was here 1434’. Van Eyck often inscribed his pictures in a witty way. This masterpiece was purchased for £600 by the National Gallery in 1842.

4. Portrait of Pope Julius II – 1511, Raphael.

Young, extraordinarily talented and what today we would call an obsessive skirt-chaser, Raphael was dead by thirty-seven. But let’s not gossip, it’s his paintings we’re interested in. The biographer Giorgio Vasari (1511-74) wrote of Raphael’s early years in Rome: ‘And at this time… he also made a portrait of Pope Julius so true and so lifelike, that the portrait caused all who saw it to tremble as if it had been the living man himself.’

Pope Julius II, Raphael, National Gallery

Julius II was as extraordinary a power as Raphael was an artist. He belonged to the della Rovere family and was a forceful pope who asserted his authority over the Papal States and expanded the power of the Papacy, by military action, to become a European power. It seems no accident that Julius named himself like Cesar. Michelangelo did a sculpture of Pope Julius in 1508 holding a sword, not a cross. He also patronised the arts, renovated Rome and ordered the rebuilding of St Peter’s in Rome.

In this portrait ‘so true and so lifelike’ Raphael breaks with compositional rules and seats Julius at an angle, not face on. It’s a lot more intimate and allows us to almost stand next to this powerful old man. This pose becomes the template for all future Papal portraits.

More in keeping with the rules of perspective the Pope’s head is centred and aligned with his hand. Everything though is conveyed through only three dominant colours.

Julius is seated in an armchair decorated with the family emblem, the acorn (della Rovere is Italian for oak). Raphael portrays him as both forceful and meditative and he is in Choir dress, not full papal regalia: white cassock, red cope (lined with ermin) and red cap. His rings are also in symbolic white, green and red: white = faith, green = hope, red = charity. Papal cross keys are visible in the green.

Julius does however look old and frail. He was in his late 60s and the Papal States were being challenged by France who controlled Bologna. You may have noticed the beard, which is unusual for a Pope. Julius had vowed not to shave it off until Bologna was liberated. No moustache though, as they were associated with Eastern Orthodox Christians, Jews and Muslims.

5. The Virgin of the Rocks – c. 1491/2-9 and 1506-8, Leonardo da Vinci.

I’ll skip the bit about the genius of Leonardo. It doesn’t need repeating, and so to the painting. Leonardo’s mysterious work here shows the Virgin Mary with John the Baptist (Jesus’s cousin) and the angel Gabriel or possibly Uriel. They kneel to adore the infant Jesus who in turn raises his hand to bless them. All are crowded in a rocky grotto lush with vegetation, the setting of which could potentially have linked to the story of Jesus, Mary and Joseph’s flight to Egypt and a mythical meet-up with John.

The Virgin of the Rocks, Leonardo, National Gallery

The Milanese Confraternity of the Immaculate Conception commissioned an alter for their new chapel in 1480. A contract was then drawn up in 1483 with Leonardo and the de Predis brothers: a central panel was to be painted by Leonardo, and two side panels with angels singing and playing musical instruments painted by the de Predis’.

The National Gallery’s painting is Leonardo’s second version of the picture. It was probably made to replace the one (now in the Louvre) that Leonardo sold because the confraternity refused to pay him adequately for it.

The Virgin of the Rocks appears to depict the type of subject that Leonardo might have painted in his native Florence, where legends concerning the young John the Baptist were popular. It’s thought Leonardo may even have planned the painting subject before receiving the commission.

In order not to confuse the characters later artists added a cross and scroll to the infant John, seen venerating the child Jesus. The Immaculate Conception is acknowledged by Mary sitting without Jesus, hence the confusion.

If you know what a Leonardo painting looks like, this looks like a Leonardo painting. How? Leonardo doesn’t put the commonly used primary colours next to each other, eg, red, blue, yellow. He also paints in layers from the drawings upwards. The painting starts with darker colours then brighter, which is what produces his famous translucency.

Leonardo didn’t paint the background, which was probably done by his students. The cavern however is Leonardo’s idea and it represents a dramatic idea of menacing darkness but with marvellous things within. The figures are emerging from this darkness.

Even though Leonardo didn’t paint everything there is clearly a ‘house style’ in his workshop. This inevitably leads to questions of authorship. Arguments have raged for decades over which bits are by Leonardo’s own hands – conveniently it’s now agreed most of it. Interestingly elements of the painting are also unfinished (see different parts of the sky, toes and hands). The Virgins cloak of ultramarine cracked because walnut and linseed oil were often mixed into paint and it didn’t dry well. Leonardo didn’t leave enough time between painting layers. Even geniuses make mistakes.

This painting was heavily restored in 2008-10. Under x-ray the restoration revealed under-drawings and a different composition: the Virgin was posed with an outstretched left arm and another angel was on the right. Jesus and Mary were drawn interacting more whereas in this final version the focus is on Jesus and John the Baptist. This alteration may have reflected changing religious fashions in 15th century Italy.

6. The Entombment – c. 1500-1, Michelangelo.

It really isn’t often you get to see a Michelangelo painting outside Italy and this is perhaps one of only three of his surviving panel paintings. It shows Jesus’ body being carried to his tomb, or sepulchre, surrounded by those supposed to have been witnesses. It may have been painted for a funerary chapel in the church of San Agostino, Rome and commissioned in 1500. It was left unfinished (it’s not known why) when Michelangelo returned to Florence the following year. The similarly unfinished Manchester Madonna is displayed next to The Entombment.

The Entombment, Michelangelo, National Gallery

Because of its unfinished state there is an almost dream like quality to some of the figures, which has led to much theological debate. The painting was intended to be seen from below, which may explain the weird way we see the paintings figures straight-on. It does give us a window into Michelangelo’s technique, which seems to be to complete each figure – as much as possible – rather than sketch the entire painting before applying the paint.

There has always been disagreement over the identity of the various figures, but this is the consensus:

- Jesus: how is his body being supported? It seems weightless. Jesus is not only being lifted into the tomb but presented to the viewer. He is also upright, which was unusual and this may be an allusion to the resurrection. The green hue of Jesus’ body – incomplete with no wounds – was the normal colour to signify dead flesh. No green paint is actually used.

- Mary Magdalene (bottom left) is incomplete. She would probably have been holding her attribute, a jar of ointment, although a drawing by Michelangelo in the Louvre is thought to be a preparatory study for this figure and shows Mary with the crown of thorns and the nails with which Jesus had been crucified. Mary anointed Jesus at Bethany and is the only follower mentioned in all four Gospels.

- Saint John the Evangelist is usually shown in red with long hair and this is probably the standing figure on the left. He is the writer of the Gospel of St John and with his brother James was an early follower.

- Joseph of Arimathea is supporting Jesus. He gave up his own tomb for Jesus.

- The priest Nicodemus is standing to the right of Jesus. He helped Joseph of Arimathea prepare Jesus’ body for burial. He wasn’t a disciple but became a follower after the crucifixion.

- Mary Salome stands to the right. She was said to have been at the crucifixion and later to have witnessed the empty tomb. She is not Salome, daughter of Herod. It was a common Jewish name; Shalom is the male version.

- The Virgin Mary is prepared only in outline in the bottom right corner, incomplete because Michelangelo may have been waiting for lapis lazuli for the Virgin’s heavenly blue cloak.

- The unfinished outline on the top right is meant to be figures carrying a slab of stone to seal the tomb.

7. The Ambassadors – 1533, Hans Holbein the Younger.

If there was one thing English monarchs were very good at during the 1500s and 1600s it was securing the employment or freelance skills of the greatest painters in Europe. During the 1520s-40s Hans Holbein the Younger worked for Henry VIII, and members of the royal court, leaving us a remarkable collection of paintings and drawings.

This large, unique painting memorialises two wealthy and powerful young Frenchmen; one a diplomat and the other a bishop. On the left is Jean de Dinteville, aged 28, French ambassador to England in 1533. To the right stands his friend, Georges de Selve, aged 24, Bishop of Lavaur, who acted on several occasions as an ambassador for the French king, the Venetian Republic and the Holy See.

The Ambassadors, Holbein, National Gallery

De Dinteville commissioned the painting during de Selve’s short visit to England from April – June 1533. This is Holbein’s first full length double portrait, which in itself is a rarity and the identities of both men were only established in 1900. De Dinteville had taken it back to France with him and it had spent 350 years away from the public gaze before arriving in England. On de Dinteville’s dagger is his age: 29th year, and on the book under de Selve’s elbow is his age: 25th year.

Despite being two Frenchmen painted by a German this is a truly ‘London’ work of art. It was posed for at the Bridewell Palace near the River Fleet, a long-gone royal palace where ambassadors lived and based their delegations. De Dinteville was unhappy to be in England and especially with its weather. But he is trusted by the French king Francis I and is in London to report back on Henry VIIIs marriage to Anne Boleyn. He even stayed on to become the godfather to their child Princess Elizabeth. The Reformation in England has also begun and on this De Dinteville can also observe and report back to Francis I. De Selve is in England possibly to deliver a message to De Dinteville from Francis I.

The painting is both a celebration of the men’s friendship and a reminder of the vanity of human accomplishments. Symbolism and allegory are everywhere. Let’s begin with the most famous and mysterious of these. In the lower foreground is the distorted image of a skull, a symbol of mortality, a memento mori. It possibly symbolises De Dinteville’s lack of vanity, which the rest of the painting does not shy away from. When seen from a point to the right of the picture the distorted skull is corrected. The crucifix, half obscured top left, holds out hope for redemption and salvation.

The clothing both men wear is luxurious. De Dinteville wears pink satin and linx fur. His gold dagger in a scabbard with blue tassles would have glistened with gold, each thread painted by Holbein. De Selve wears a patterned robe of woven silk damask with fur lining. The picture is also in a tradition showing learned men with books and instruments. Although much in this painting also seems to point to religious upheaval in Europe.

The objects on the upper shelf represent heavenly bodies: a celestial globe (the night sky), a portable sundial and various other instruments used for understanding the heavens and measuring time and the calendar. Holbein was friend to the king’s German astronomer Nicholas Kratzner; the objects may have been his.

The objects on the lower shelf represent earthly matters: a lute with one string broken, perhaps representing the Roman Catholic/Protestant discord; a case of flutes where one is missing, perhaps symbolising religious disharmony; a book of arithmetic which has opened on the division page perhaps further representing the division in Christianity; a hymn book which is German Lutheran, perhaps emphasising de Selve’s efforts to seek accommodation with the Protestants; and a terrestrial globe that has stopped at Polisy where de Dinteville owned a chateau.

8. A Young Woman standing at a Virginal – c. 1670-2, Johannes Vermeer.

Vermeer made very few paintings and only about thirty six survive today. Nearly all of them depict young women in calm, domestic interiors and often they are playing musical instruments, either alone or in the company of others. This was a popular subject in 17th century Holland. Sometimes the themes were bawdy, with tobacco and alcohol, then thought of as aphrodisiacs. Sometimes they appear entirely innocent and sometimes, as here, the implications are open to debate.

Young Woman standing at a Virginal, Vermeer, National Gallery

The well-dressed woman playing a virginal (a small harpsichord) stands in a prosperous Dutch home. Love is the undeclared theme. She is holding our eye with a direct gaze, suffused in the light which streams through the window. Is she caught in a moment of expectation or uncertainty? Perhaps we have interrupted her playing or perhaps she is waiting for us or even someone else.

There are two paintings on the wall behind her. The small landscape on the left, and the painting decorating the lid of the virginal, resemble works by Vermeer’s Delft colleague Pieter Groenewegen. Wealthy Dutch households would often display painted landscapes.

The second painting, attributed to Cesar van Everdingen, shows Cupid holding a card. It represents love and fidelity, either referring to the idea of faithfulness to one lover or, in conjunction with the virginal, to the traditional association of music and love. Musical gatherings were popular, respectable social activities. But they were also a good way for young people to meet so there was always potential for flirtation, or an excuse for something more risqué.

The empty chair in the foreground invites us in. It could symbolise an absent love, perhaps a merchant overseas or a lover, the person she hopes will enter the room and sit on the chair. Vermeer always seems to leave open the virtue of the women concerned, but he rarely gives us enough clues to help us come to a firm conclusion.

Vermeer’s painting also tells us a lot about the woman’s social status. She’s dressed in fine silks and a pearl-studded necklace. She is clearly in the living room of a prosperous Dutch home, with paintings, a marble-tiled floor and a skirting of locally produced Delft blue and white tiles. The white walls help create this silent, calm inner-space.

Vermeer uses light in most of his paintings to disperse and emphasise at the same time. Detailing is picked out in the shadows and in the stream of sunlight through the window. Vermeer often put paintings into his paintings. There are lots of parallel and horizontal lines creating a pure compositional geometry.

This painting can be related to another Vermeer in the National Gallery, ‘A Young Woman seated at a Virginal’.

9. The Supper at Emmaus – 1601, Caravaggio.

This painting represents the moment of ‘divine recognition’ from a New Testament story. On the third day after Jesus’s crucifixion two of his disciples were walking to Emmaus near Jerusalem when the resurrected Jesus himself joined them, but they didn’t recognise him! At supper that evening in Emmaus ‘he took bread, and blessed it, and brake and gave to them. And their eyes were opened, and they knew him; and he vanished out of their sight’ (Luke 24: 30-31).

Caravaggio’s dramatic treatment of this ‘revelation’ makes it one of his most powerful works. The depiction of Jesus is unusual in that he is beardless (like in Michelangelo’s Last Judgement in the Sistine Chapel) and emphasis is given to the still life’s on the table, e.g. light passing through the carafe onto the tablecloth and the bowl of fruit.

Supper at Emmaus, Caravaggio, National Gallery

The intense surprise of Jesus’ disciples is conveyed through their body language and expressions. The viewer is also made to feel like a participant, particularly as the figure on the right (St Peter) and the left (Cleophas) almost puncture the canvas towards us.

Caravaggio has shown the disciples as ordinary working men, with bearded, lined faces and humble clothing, in contrast to the youthful beardless Jesus who, with his long hair, red tunic and more classical attire seems literally to have come from a different age. The disciple on the right wears a scallop shell, symbol of a pilgrim (in Caravaggio’s day). Caravaggio was famous for still life’s and a bowl of fruit is almost toppling off the table. Here it represents the fragility of life, always in the balance.

Caravaggio uses contrasts of light and shade (known as chiaroscuro) to heighten the drama. A strong light from the left falls on the faces of Jesus and the disciple on the right, casting a shadow on the wall behind him, almost like a reverse halo, and illuminates the hand which the disciple thrusts towards the viewer. If the shadow were to remain accurate the innkeepers face would be cast over Jesus’ face, but it remains in light. The light represents the light of recognition too. The innkeeper is in the dark literally and spiritually.

The triangular structure of the figures directs our eye into picture. The back view of the disciple on the left, and the other disciple’s outstretched arms, shown in extreme foreshortening, act like lines focusing our attention on Jesus’s face mid-blessing.

The picture was commissioned by the Roman nobleman Ciriaco Mattei in 1601. Caravaggio painted a second, more subdued version of Supper at Emmaus about five years later, now displayed in Milan.

After arriving in Rome in 1592 Caravaggio worked as a hack painter, selling his work almost off the railings. He did a lot of still life’s during this period and street scenes using local people as models. The models in Supper at Emmaus are not well known although we do know the model for Jesus was a male prostitute.

Caravaggio had no workshop and left no drawings. He didn’t travel around Europe (until he went on the run after committing a murder during a fight in Rome) but his fame and influence grew. He is the only artist with a school of art named after him, known as Caravaggionism.

10. Rain, Steam and Speed – 1844, Joseph Mallord William Turner.

We started this blog with the Wilton Diptych and it’s only taken 450 years to feature another painting by a British artist. There are many who regard London born Turner (he was born in Maiden Lane, a few hundred yards away from the National Gallery) as Britain’s greatest painter. He was a talent from childhood and became famous for his large ‘sublime’, dramatic land and seascapes. In later life though he became a more revolutionary painter.

In this truly ‘impressionistic’ work a steam engine is coming at us as it speeds over a bridge through driving rain. The bridge is the Maidenhead Viaduct which crosses the Thames between Taplow and Maidenhead on the Great Western line to Bristol. Designed by Isambard Kingdom Brunel, the viaduct was in use from July 1839. We are looking east towards London as the train heads towards the west of England.

Rain, Steam and Speed, Turner, National Gallery

The engine is pulling a train of unroofed goods-wagons in which passengers, paying the cheapest rates, could travel. Very soon William Gladstone’s ‘Railway Act’ 1844 would create one penny travel and roofs for all passenger carriages. Average speed on the Great Western Railway (GWR) in 1844 was 33 mph but on long level stretches, such as the Maidenhead Viaduct, an unheard of 60 mph could be reached – faster than a galloping horse.

Railway mania was sweeping Britain. In 1844 there were 2000 miles of track; by 1848 there were 5000 miles of track. The landscape was being altered and time was being regulated – all towns and cities now conformed to train timetables. Trains also brought new concerns (speed, technology, crashes) and they destroyed landscapes.

What was Turner’s attitude toward the industrial progress? Possibly ambiguous, judging by this painting (and The Fighting Temeraire which is often displayed with this painting). Is Turner celebrating change, lamenting a past golden age or simply accepting and painting these changes? It’s said Turner himself liked the convenience of train travel.

Turner’s painting is also full of allegory and symbolism:

Time:

- Past – is gone. There is nothingness behind the train.

- Present – where the train is. But look quickly or it will be gone.

- Future – where the train is going.

The four elements:

- Earth – the fields.

- Water – the River Thames.

- Air – the sky.

- Fire – the train engine.

The arched bridge on the left was built in the 1770s. Until the railways horses and coaches on roads were the fastest way to travel. A ‘swift’ hare is leaping across the rails: nature in conflict with technology. In superstition a hare also foretells tragedy: ‘hare before, trouble behind’.

A skiff passes gently on the river, in the opposite direction. As a young artist Turner often viewed and painted from boats and used a parasol. There is a man in a field with a horse and plough, facing away from the train. The women in white dresses hark back to figures in traditional landscapes.

This painting was exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1844. It presented a new way of painting trains. Before this they had been represented from the side-on and fairly static. Turner’s painting was shocking, sensational and successful. The critic John Ruskin claimed the origins of the painting derive from a train journey Turner took in a storm. He stuck his head out of the moving train window and reproduced the strong sensations in this painting. It’s easy to believe.

11. Bathers at Asnières – 1884, Georges Seurat.

This huge picture was Seurat’s first major composition, painted when he was only twenty-four. He died age thirty-one. He intended it to be his grand debut and a work with which he would make his mark at the official Paris Salon. It shows several men and boys relaxing in the sun on the banks of the River Seine, between the bridges at Asnières and Courbevoie, just north-west of central Paris.

The men and boys on the riverbank are as immobile as sculptures and Seurat shows them in profile, as if in a frieze, their smooth bodies defined by unbroken outlines. Although they occupy the same small area of riverbank, each seems absorbed in his own thoughts or activity, none engaging with each other or with us.

Bathers at Asnières, Seurat, National Gallery

In the background is a railway bridge that partly hides a parallel road bridge, as well as the chimneys of the gas plant and factories at Clichy, where some of the men may work. Recreational sailboats can be seen on the river.

So many elements in this painting appear to be random. Nothing could be further from the truth. It is a work of absolute harmony, pre-thought and pre-planned:

- The working-class bathers are looking across the Seine at the middle-class promenaders in Seurat’s accompanying painting ‘A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte’.

- Rule of Thirds – there are nine sections (3×3) with heads on thirds horizontal; the boats are on thirds vertical.

- Rule of Fourths – there are also sixteen sections (4×4) with mini paintings in various sections, e.g. top fourth empty of detail, boats on left or boats on right, boy with red hat.

- Diagonals – legs, bodies, riverbank, spaces between men, back of centre bather and sail on right, head of centre bather and dogs head, red hat to straw hat intersects neck of central bather.

This painting really requires careful and rewarding observation. Seurat is often called a post or neo-Impressionist. But this painting was not done in plein air or quickly or in any way portable.

Seurat drew conté crayon studies for individual figures using live models. He also made small oil sketches on site which he used to help design the composition and record the effects of light. About thirteen oil sketches and ten drawings survive. The final composition was obviously painted in the studio.

The painting was done using a cross hatch technique, not Seurat’s more famous pointillist technique, which he had not yet invented – although he did later rework areas using dots of contrasting colour to create a more vibrant, luminous effect.

Pointillism, and the cross hatch here, is paint applied in dots or small lines. The dots and lines fuse optically from a distance. Colours are painted next to each other, not on top or mixed. It’s called the Optical Mixture. Try looking up-close at this painting and then at a distance.

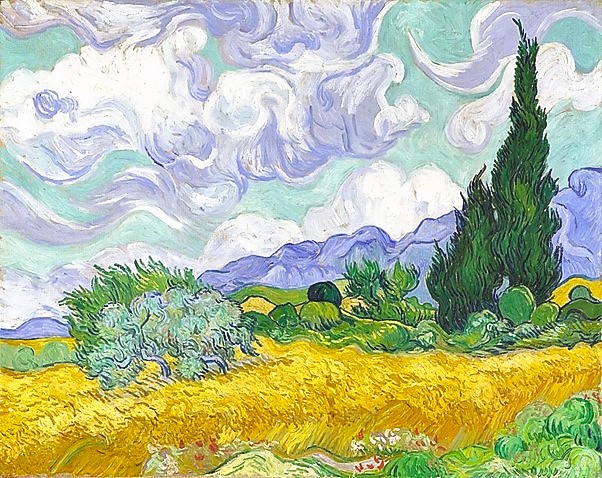

12. A Wheatfield, with Cypresses – 1889, Vincent van Gogh.

I know, I know that the super-famous Sunflowers is displayed on the same wall. But I like this one a lot more. It’s a beautiful painting. In June 1889, soon after he admitted himself as a patient at the psychiatric hospital of Saint-Paul de Mausole at St-Rémy in the south of France, van Gogh wrote to his brother Theo: ‘The cypresses still preoccupy me, I’d like to do something with them like the canvases of the sunflowers because it astonishes me that no one has yet done them as I see them. It’s beautiful as regards lines and proportions like an Egyptian obelisk. And the green has such a distinguished quality. It’s the dark patch in a sun-drenched landscape.’

A Wheatfield, with Cypresses, Van Gogh, National Gallery

Like with Sunflowers van Gogh produced several versions of A Wheatfield, with Cypresses. He was allowed out of the hospital’s grounds only if accompanied by a guardian and he painted his first version in late June 1889. In September, whilst temporarily confined to his room due to a relapse, van Gogh painted the National Gallery’s picture, his final version.

This landscape includes typical Provençal natural elements: a golden wheatfield, evergreen cypresses, an olive bush and the blue Alpilles mountains. This landscape had a symbolic meaning for Van Gogh too. The cycle from sowing to harvesting wheat – often represented by the figures of the sower and the reaper – was a metaphor, based on biblical parable, for life and death.

Writing to his sister in July, regarding people’s responses to events we cannot control or understand, he observed, ‘What else can one do … but gaze upon the wheatfields. Their story is ours, for we who live on bread, are we not ourselves wheat to a considerable extent, at least ought we not to submit to growing, powerless to move, like a plant, relative to what our imagination sometimes desires, and to be reaped when we are ripe, as it is?’

Van Gogh also wrote of painting outdoors during the summer Mistral, the strong, cold wind of southern France. The wind animates the wheat and trees and clouds and even, it seems, the distant mountains. Every element is painted with the powerful rhythmic lines and swirling brushstrokes we associate with van Gogh. He is making nature alive, dynamic and most of all incredibly expressive.