Fleet in the City: Part 2 – Holborn Viaduct

The River Fleet rises in Hampstead Heath meandering downhill through north London for four miles, until it exits into the River Thames at Blackfriars.

Holborn Viaduct – looking south where the River Fleet once flowed

From Heath to Thames the Fleet is now culverted and runs underground, incorporated into Joseph Bazalgette’s grand nineteenth century London sewer system. Its exit into the Thames is now an inconspicuous outlet rather than a wide open inlet for what had once been a navigable Thames tributary. The word ‘Fleet’ derives from the Anglo-Saxon word for ‘tidal inlet’.

The Fleet’s story for almost four hundred years has been one of decline: river to rivulet, ditch to drain. Its reputation, for Londoners, now carries no more weight than an association with Fleet Street, a busy, commercial City highway; or with Fleet Road in Hampstead, which curls along the old route.

‘Fleet in the City: Part 2 – Holborn Viaduct’ explains the monumental Victorian engineering project that was the bridge of Holborn Viaduct, with all its decoration, detail and symbolism. This extravagant structure bridges the old valley of the Fleet. In ‘Fleet in the City: Part 1’ we followed the route of the River Fleet in the City of London.

Now flowing entirely underground this old river valley is better known above ground as Farringdon Street and New Bridge Street. Holborn Viaduct bridges Farringdon Street just below Snow Hill. The thing to bare in mind is that this wasn’t just any old bridge, but a serious feat of engineering and a landmark bridge located in the heart of the British Empire.

Holborn Viaduct

Holborn Viaduct – looking north

It was all about modernisation and it started with sewage: human effluence, household waste, animal remains and traders’ detritus. The offscourings of millions of Londoners found their way into London’s rivers. It was choking the city, polluting the waterways and killing its citizens. When the ‘Great Stink’ of 1858 disrupted Parliament, almost bringing it to a grinding halt, Government at last took notice. Civil engineer Joseph Bazalgette proposed the building of a new sewer system with co-ordinated drainage and by the 1860s his massive construction project was well underway. You could argue that Joseph Bazalgette did as much for London under ground as Christopher Wren had achieved above it.

Within the City the remaining section of Wren’s canalised River Fleet was culverted (see Part 1), driven under ground to integrate with the sewer system and replaced with wide thoroughfares stretching north to the new railway terminal at Kings Cross. On some stretches the river had become no more than a stinking muddy ditch. Charles Dickens had already set Fagin’s lair nearby in ‘Oliver Twist’. These hovel strewn lanes would be wiped out during slum clearances making way for Farringdon Road, London Underground and Holborn Viaduct.

The project covering this part of the City of London was known as the Holborn Valley Improvements. William Heywood, Surveyor and Engineer to the City Commissioners of Sewers, designed the Viaduct and the idea was not only to bridge the valley but to connect the two parts of the City by road. The Viaduct would join Newgate Street in the east to Holborn in the west at a new junction at Holborn Circus. A new direct route from Leadenhall Street to Marble Arch would now connect the City to the West End.

Construction

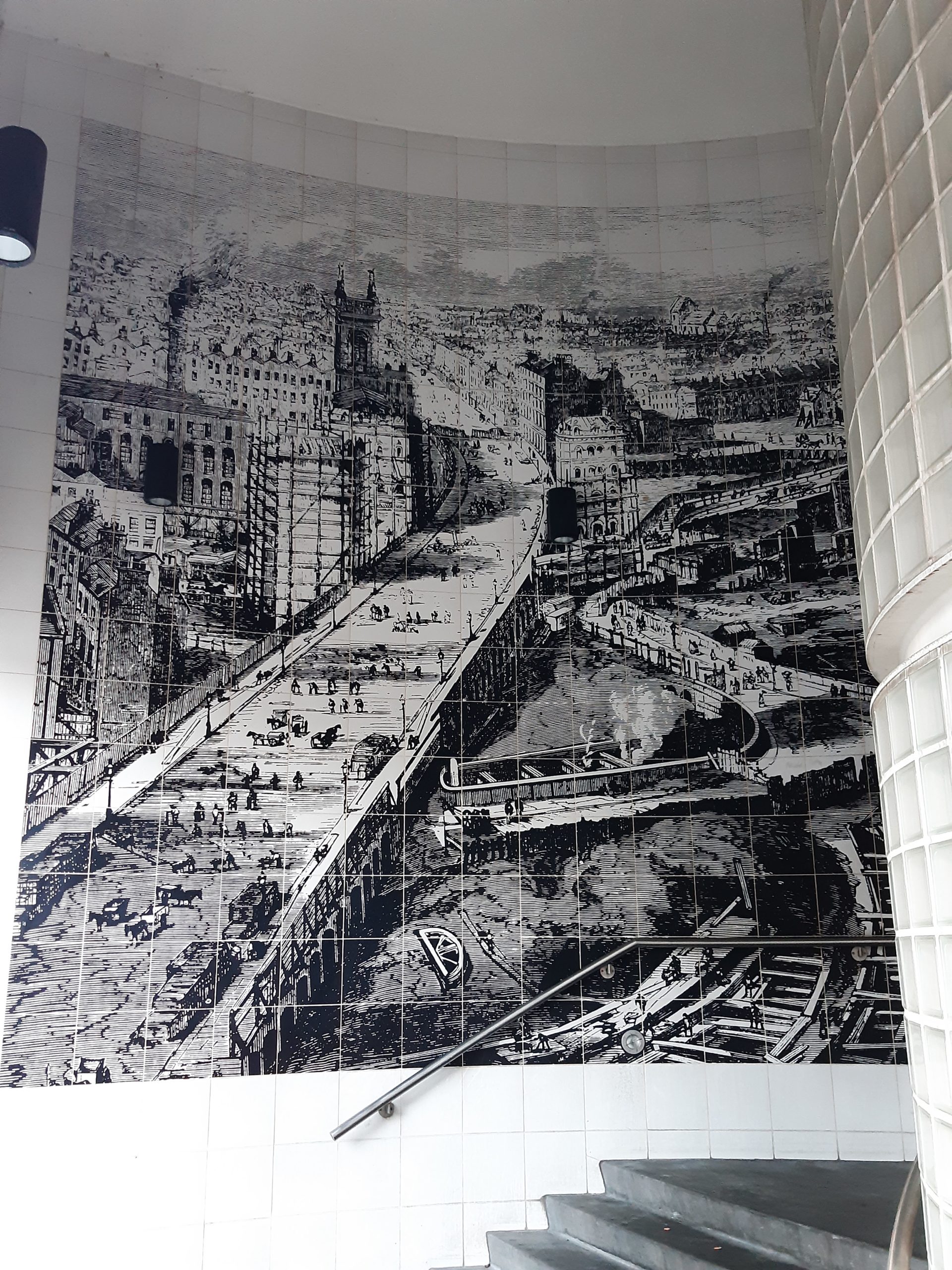

Holborn Viaduct: Mural, looking west – NW building steps

Construction began in June 1867 and was completed on 6th November 1869, when the Viaduct was officially opened by Queen Victoria – she also opened the rebuilt Blackfriars Bridge at the same time. The Viaduct is 1400 ft long (427m) and 80 ft wide (24m). The east part stands on what was Skinner Street and the west part on what had been Holborn Hill. Including the construction of St Andrews Street, St Bride Street and the west side of Charterhouse Street the cost was just over £2 million.

The Viaduct bridge is just one part of the entire vaulted causeway. It has three spans and is constructed of six parallel arches stretching over the road with shorter arches over the pavements. Octagonal granite piers and pilasters support the Viaduct. Stonework is Portland stone. The bridge itself is cast-iron with some iron decoration. The gilded decorations on the outsides feature roundels with dragons and helmets which are emblems on the City Arms. Floral and foliage patterns feature in-between. City Arms are positioned centrally on each parapet.

Office buildings designed in the Italian Gothic style stand on each corner. The two southern buildings are original. The northern buildings were bomb damaged in the Second World War and rebuilt. The keystones at ground level above the arches of each building feature river gods. Two Atlantes support each of the four balconies on the second floors. Steps from ground level in each building lead up to the Viaduct.

The steps in the NW building display a superb, tiled artwork of this colossal civil engineering project in progress, essentially a copy of a contemporary illustration.

Statues and Sculptures on the Viaduct.

On each of the corner buildings there is a niche facing the upper level of the Viaduct. In each niche is a 2m high stone figure of a man deemed crucial to the development of the City of London.

Henry Fitzailwyn – SW Building

Fitz Eylwin (as spelled on this statue) was the first Mayor of London. He was in office continuously from 1189 until 1212, the only Mayor who served for life.

William Walworth – NW Building

Walworth served twice as Lord Mayor (as the position was now called) in 1374-5 and 1380-81. He is probably most famous for killing Wat Tyler, leader of the Peasants Revolt, with his dagger during Tyler’s meeting with Richard II at Smithfield, which is just around the corner.

Holborn Viaduct: Henry Fitzailwyn and the Atlantes holding up the balcony

Holborn Viaduct: William Walworth

Thomas Gresham – SE Building

Gresham was a successful merchant who, inspired by the bourse in Antwerp, established the Royal Exchange in London in 1565. If you see a grasshopper featured on any City building it is the Gresham family symbol.

Hugh Myddleton – NE Building

Myddleton was not only Royal Jeweller to James I, but became the main funder and driving force for the construction of the New River (completed 1612); a project designed to bring fresh drinking water into London from Hertfordshire.

Holborn Viaduct: Thomas Gresham

Holborn Viaduct: Hugh Myddleton

Along the pavement of the Viaduct are four 2.4m high bronze female statues representing values and attributes which embody both classical learning and modernity, but with a very Anglocentric worldview.

Fine Art – NW Parapet

Dressed in classical robes she holds a crayon in her right hand and a drawing board with paper in her left hand. This represents design. Her left foot rests on an Ionic column, for architecture. Behind her is a Corinthian column on top of which rests a bust of Pallas Athena, for sculpture.

Science – NE Parapet

This classically robed figure appears more formal than the Fine Arts. She symbolises Modern Science and is holding the ‘Governors of the Steam Engine’, a crucial part of an engine which had been at the cutting edge of British technological ingenuity.

Behind her on a tripod are the signs of the zodiac and a globe encircled by an Electric Telegraph wire. Beneath the tripod is a compass and geometrical drawings, one of which is Pythagoras’s theorem.

Holborn Viaduct: Fine Art

Holborn Viaduct: Science

Commerce – SW Parapet

A mural crown sits on her head representing the City of London and its ancient walls. The Union Flag and City Arms are on the back of her cloak. Her right hand is open as a sign of welcome to mankind. Her left hand holds gold, ingots and coin which represent enterprise and commerce in a civilised world. Keys at her feet symbolise the Freedom of the City of London. Maritime objects represent trading ships.

Agriculture – SE Parapet

She wears a crown of olives, the ‘emblem of peace’. Oak leaves fringe her robe. On her left side corn and poppies grow. In her right hand she holds a sickle and at her feet is a belt and sheath containing a whetstone.

Winged Lions – N and S Parapet

The Winged Lions rest their paws on a globe. Winged lions stretch all the way back to ancient Assyrian Lamassu, the Book of Daniel and St. Mark the Evangelist. Lions were also a symbol of Great Britain, and these winged lions are dominating the entire globe.

All four of the original designs for the stone statues are by Henry Bursill. Bursill also designed Agriculture and Commerce. Farmer & Brindley designed Fine Art, Science and the Winged Lions.

Holborn Viaduct: Commerce

Holborn Viaduct: Agriculture

Holborn Viaduct: Winged Lion

Holborn Viaduct: Dragons

Holborn Viaduct: looking north. SW Building on left with river gods over keystones and Atlantes supporting balcony.

Holborn Viaduct: looking south